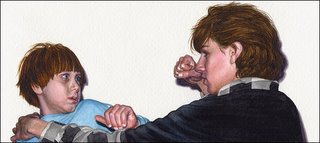

The old-fashioned sibling rivalry isn't like it is today. Today it is called violence. It is called battery. Does this behavior breed future violent criminals?

From infancy until he reached the threshold of manhood, the beatings Daniel W. Smith received at his older brother's hands were qualitatively different from routine sibling rivalry. Rarely did he and his brother just shove each other in the back of the family car over who was crowding whom, or wrestle over a toy firetruck.

Instead, Mr. Smith said in an interview, his brother, Sean, would grip him in a headlock or stranglehold and punch him repeatedly. "Fighting back just made it worse, so I'd just take it and wait for it to be over," said Mr. Smith, who was 18 months younger than his brother. "What was I going to do? Where was I going to go? I was 10 years old."

To speak only of helplessness and intimidation, however, is to oversimplify a complex bond. "We played kickball with neighborhood kids, and we'd go off exploring in the woods together as if he were any other friend," said Mr. Smith, who is now 34 and a writing instructor at San Francisco State University. (Sean died of a heart attack three years ago.)

"But there was always tension," he said, "because at any moment things could go sour."

Siblings have been trading blows since God first played favorites with Cain and Abel. Nearly murderous sibling fights — over possessions, privacy, pecking orders and parental love — are woven through biblical stories, folktales, fiction and family legends.

In Genesis, Joseph's jealous older brothers strip him of his coat of many colors and throw him into a pit in the wilderness. Brutal brother-on-brother violence dominates an opening section of John Steinbeck's "East of Eden," and in Annie Proulx's short story "Brokeback Mountain," the cowboy Ennis del Mar describes an older brother who "slugged me silly ever' day."

This casual, intimate violence can be as mild as a shoving match and as savage as an attack with a baseball bat. It is so common that it is almost invisible. Parents often ignore it as long as nobody gets killed; researchers rarely study it; and many psychotherapists consider its softer forms a normal part of growing up.

But there is growing evidence that in a minority of cases, sibling warfare becomes a form of repeated, inescapable and emotionally damaging abuse, as was the case for Mr. Smith.

In a study published last year in the journal Child Maltreatment, a group of sociologists found that 35 percent of children had been "hit or attacked" by a sibling in the previous year. The study was based on phone interviews with a representative national sample of 2,030 children or those who take care of them.

Although some of the attacks may have been fleeting and harmless, more than a third were troubling on their face.

According to a preliminary analysis of unpublished data from the study, 14 percent of the children were repeatedly attacked by a sibling; 4.55 percent were hit hard enough to sustain injuries like bruises, cuts, chipped teeth and an occasional broken bone; and 2 percent were hit by brothers or sisters wielding rocks, toys, broom handles, shovels and even knives.

Children ages 2 to 9 who were repeatedly attacked were twice as likely as others their age to show severe symptoms of trauma, anxiety and depression, like sleeplessness, crying spells, thoughts of suicide and fears of the dark, further unpublished data from the same study suggest.

No comments:

Post a Comment